Understanding the Value of the Empathic Dimension in Design

Maria V Miller

Iowa State University

2016 Harvey Mudd Design Thinking Workshop

Summary

As we continue to face the challenge of increasingly diverse multidisciplinary working groups, there is an urgent need to cultivate a better awareness of our differences, not just in terms of ethnicity, gender, nor cultural background, but in terms of differing cognitive profiles. Such an understanding would go a long way toward engendering mutual respect and appreciation for the value that different thinking styles bring to the design process. Understanding difference in terms of cognitive profiles also has the potential to encourage a culture of tolerance and appreciation of others, inspiring a greater willingness to cooperate. As design educators, this increased awareness could also serve to better engage and retain students in the design disciplines. Empathizing-systemizing theory has the potential to open the door to an important and necessary conversation in design thinking. Design thinking as a formal method of creative problem solving has been traditionally defined by our understanding of analysis versus synthesis and convergent versus divergent thinking. My research however, seeks to explore systemizing- empathizing theory as a more wholistic framework for better understanding and defining design thinking and implementing better design-thinking practices in studio and subsequently in practice.

I will hence critically examine Baron-Cohen’s theory and methods, as the leading thinker on Empathizing (EQ)-Systemizing (SQ) theory and situate this knowledge within the context of theory concerned with the contemporary design process and its traditional lack of diversity, both in terms of diverse background, but also in terms of diversity in design thinking and cognitive styles. My intention is to determine through a series of studies of design studio, the existence of modes of thinking and designing that have value to the profession but are currently unrecognized and under supported by educators and professional practice. The importance of this sort of study to the profession is without measure: we have a deeply gendered and non-representational profession even now in the C21st and yet we also misunderstand gender. This research goes beyond notions of gender difference, to question much deeper ideas of difference at the level of our relationship to the material world and to others.

Introduction

Empathizing–systemizing theory can be best understood as a spectrum along which people may be classified on the basis of their scores for strength of interest in empathy and systems. Here, empathizing is defined as the drive to identify others’ mental states in order to predict their behavior and respond with an appropriate emotion, while systemizing is defined as the drive to analyze a system in terms of the rules that govern the system, in order to predict its behavior.i Developed by Simon Baron-Cohen, Empathizing-Systemizing theory has been proven to be an excellent predictor of students who choose STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and the

Humanities. Findings suggest that individuals in the sciences possess a cognitive style that is more systemizing-driven than empathizing-driven, whereas individuals in humanities possess a cognitive style that is much more empathizing-driven than systemizing-driven.ii

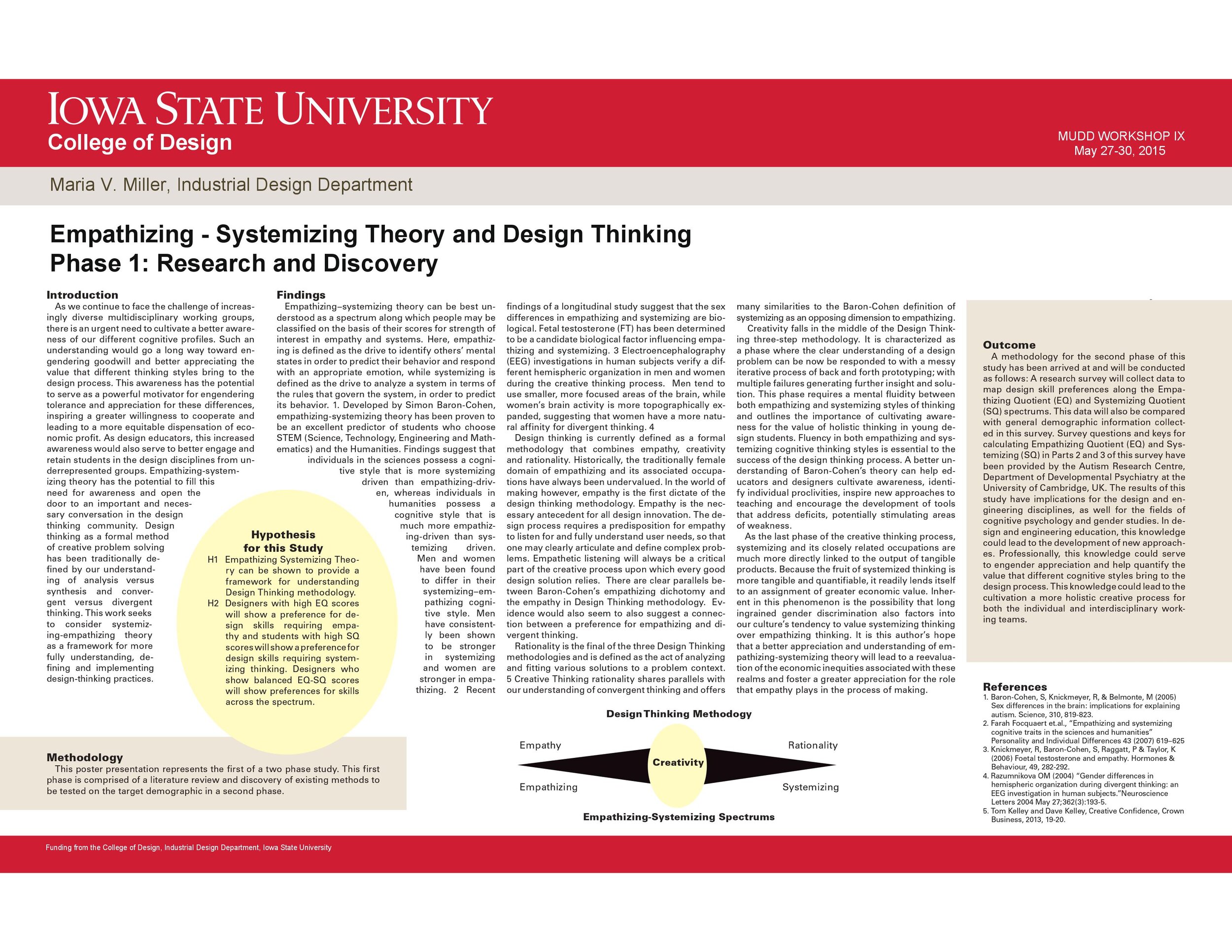

Men and women have also been found to differ in their empathizing-systemizing cognitive style. Men have consistently been shown to be stronger in systemizing and women are stronger in empathizing.iii Recent findings of a longitudinal study suggest that the sex differences in empathizing and systemizing are biological. Fetal testosterone (FT) has been determined to be a candidate biological factor influencing empathizing and systemizing.iv Electroencephalography (EEG) investigations in human subjects verify a different hemispheric organization in men and women during the creative thinking process. Men tend to use smaller, more focused areas of the brain, while women’s brain activity is more topographically expanded, suggesting that women may have a more natural affinity for divergent thinking. Design thinking is currently defined as a formal method that combines empathy, creativity and rationality. Historically, the traditionally female domain of empathizing and its associated

occupations have always been undervalued. In the world of making however, empathy is the first dictate of design thinking methodology and the necessary antecedent for all design innovation. The design process requires a predisposition for empathy to listen for and fully understand user need, so that one may identify, anticipate, articulate and define complex design opportunities in need of a good solution. There are clear parallels between Baron-Cohen’s empathizing dichotomy and the empathy in design thinking methodology. Evidence would also seem to suggest a connection between a preference for empathizing and divergent thinking.

Rationality is the final of the three design thinking methodologies and is defined as the act of analyzing and fitting various solutions to a problem context.vi Creative thinking rationality shares parallels with our understanding of convergent thinking and offers many similarities to the Baron-Cohen definition of systemizing as an opposing dimension to empathizing.

Creativity falls in the middle of the design thinking three-step methodology. It is characterized as a phase where the clear understanding of a design problem can be now be responded to with a messy iterative process of back and forth prototyping; with multiple failures generating further insight and solution. This phase requires a mental fluidity between both empathizing and systemizing styles of thinking and outlines the importance of inspiring awareness for the importance of cultivating a more holistic thinking in young design students.

Outcomes

The results of this study have implications for the design and engineering disciplines, as well for the fields of cognitive psychology and gender studies. In design and engineering education, this knowledge could lead to the development of new approaches. Professionally, this knowledge could serve to engender appreciation and help quantify the value that different cognitive styles bring to the design process. This knowledge would potentially contribute to the cultivation of a more wholistic creative process for both the individual and multidisciplinary working teams. It could also lead to an

increased appreciation for the empathizing cognitive style as essential to innovation and the design process, potentially supporting a case for greater parity of economic remuneration for design skill specializations shown to fall within this realm.

Methods

Methods adopted will be both quantitative and qualitative to address the broad depth and wealth of information that can be gleaned from the day-to-day activities in the design process. The initial phase of this research will compare the results of EQ (Empathizing) and SQ (Systemizing) scores with preferences for the different skills inherent to the design process, such as working with color, form, materials, details, connections, writing, diagraming, gathering research, programming, etc. This research survey will collect data to map design skill preferences along the Empathizing (EQ) and Systemizing (SQ) spectrums and be compared with demographic information. There is no direct benefit to research survey participants. This survey will take between 15-20 minutes to complete. Participation is entirely voluntary and participants may withdraw at any time. These results will serve as a foundation for further exploring empathy as economically vital to the design process as well as uncovering data in which the value of empathy can be potentially better quantified.

Impact of the Study

Systemizing is the last phase of the creative thinking process and its closely related occupations (STEM) are much more directly linked to the output of tangible products. Because the fruit of systemizing thinking is more tangible and quantifiable, it readily lends itself to an assignment of greater economic value. Inherent in this phenomenon is the possibility that long ingrained gender discrimination may factor into our culture’s tendency to value systemizing thinking over empathizing thinking. A better appreciation and understanding of empathizing-systemizing theory might lead to a reevaluation of the economic inequities associated with the skills that fall within each of these realms and foster a greater appreciation for the role of empathy in the process of making. Plotting design skill preferences along the Empathizing-Systemizing spectrum would be the first step toward better understanding and quantifying the value of empathy in the making process, potentially leading to greater economic equity.